Growing & Razing an Argument: the 'Tree of Reasoning' strategy explained

When they first arrive on our doorstep, our students are convinced that they're masters of argumentation:

(For a humorous way to show your students what an argument ISN'T, check out Monty Python's Argument Clinic!)

So confident they are (I say this in love), that when we tell them we're going to write argumentative essays this year, they challenge our very intelligence and purpose altogether:

"'Persuasive,' Miss, you mean persuasive essays. We learned those in middle school."

...to which the next student replies: "Yeah, we already learned this in middle school, Miss. Why do we have to do it again?!"

...before the final student jumps in: "I love arguing! Last year, I made Sally cry during our debate. It was awwwesome!"

Don't get me wrong...our writers certainly DO have an argumentative foundation somewhere in there by the time they reach us, but they still have a long way to go before they understand the full scope of its power. By the time they step into the real world, our students need to be adept at argumentation, so we're going to build on these roots to get them there.

Today's post is going to offer two different classroom activities that will help students better understand what is meant by 'Line of Reasoning' (LOR). Once they know what a LOR is and what makes it strong, they'll be able to advance their overall approach to writing argumentatively.

When most people hear a good speech, their brains can automatically decide for them, "Man, that was a GOOD speech!" but not everyone can articulate why that speech was so darned good in the first place.

Take Martin Luther King, Jr.'s "I Have a Dream" speech as an example. The weight of Dr. King's words are viscerally felt, but few people will credit those chills on their arms to his clever use of anaphora or his mind-blowing employment of parallel structure, or that he topped it all off with an alliterative beat drop at just the right moments...

Same deal when we're observing an argument. Most of our students will be like, "man, that guy killed it!", but articulating why he killed it is a whole other skill set they have yet to learn.

If our writers are going to learn to argue, they should probably know the working parts of an argument in order to understand what makes it whole.

Once they begin to see what's happening behind the scenes of that argument, they'll start seeing their own work in those terms.

For young writers, this is kind of easier said than done, though...(the minute I start uttering words like claim, warrant, and Toulmin, they get that glazed look in their eyes!).

So where do we begin? One strategy is to simply start from the ground up...

The Tree of Reasoning

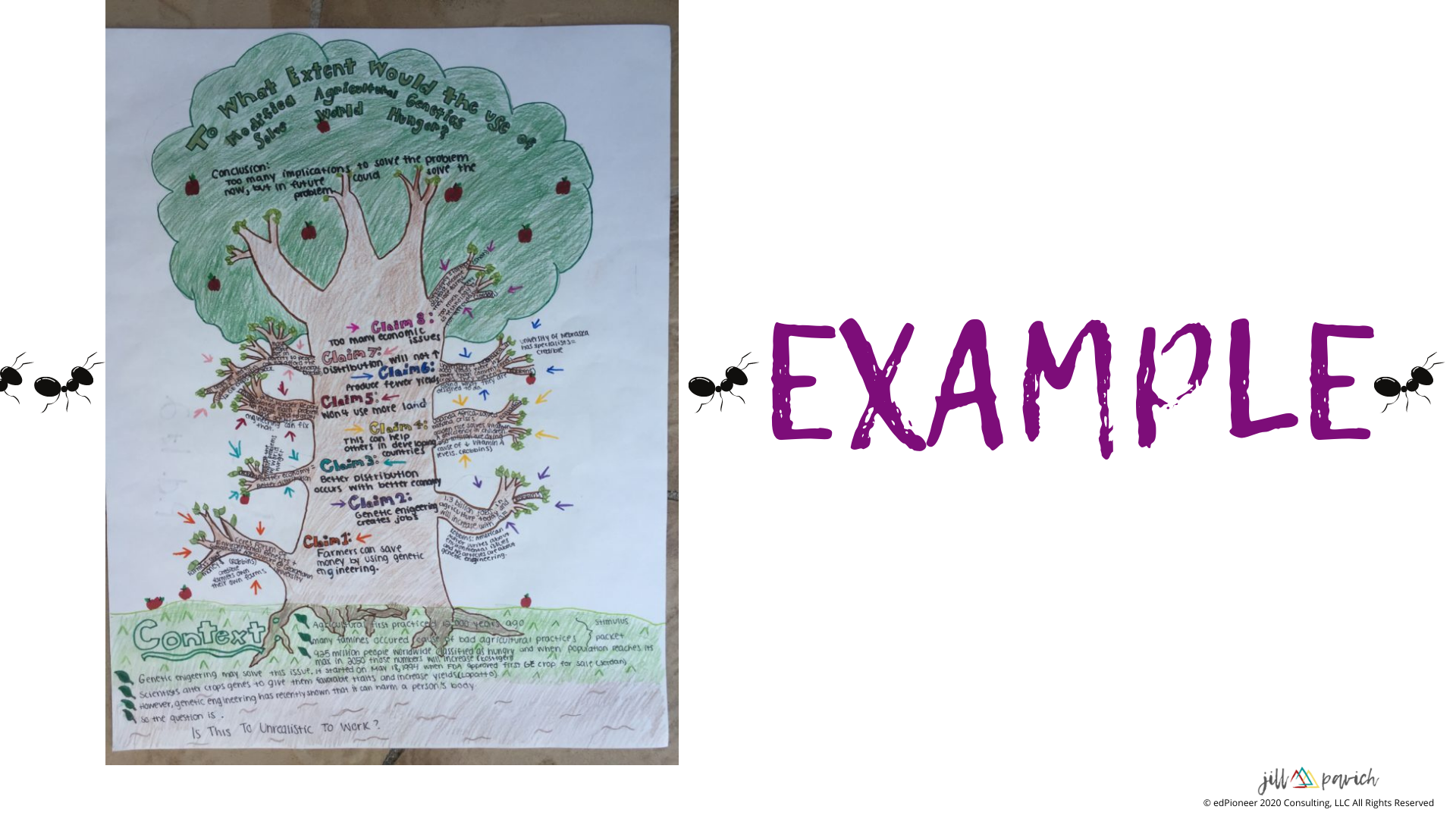

The Tree of Reasoning is such a hit with young writers because it helps them 'see' what a line of reasoning actually is. And that's because this strategy asks students to literally illustrate what an argument looks like in concrete form.

Ultimately, they can apply the 'tree' concept I'll share with you momentarily in lots of different ways, such as to illustrate:

- a well-known, published argument (a famous speech, a TED Talk, etc.)

- their own intentions for arguing (as a form of brainstorming)

- their argument after it's written (as a means of self-assessment)

- a peer's argument (as a form of peer editing)

Before they start drawing their own, happy little trees, I recommend warming them up by breaking down the component parts of other people's arguments first.

So for instance, I like to start small by having them illustrate the two sides of those little "Debate" articles in the back of Scholastic's Upfront magazine. It helps them get familiar with the two perspectives featured, how they develop their points, and it gives them a sense of accomplishment to start because the exercise is a quick-digest. Then we move on to lengthier work from there.

The scaffold they apply to these arguments?

Behold, the Tree of Reasoning...

Pretty awesome, right?! First of all, kudos to my dear friend, Beth Rubin for sharing this super awesome classroom practice with me, because not only did I get to enjoy the fruits it yielded (literally...some of my kids drew apple trees, mango trees, palm trees), but now I get to share it with all of you! Oh, snap!

Here are some slides to help you and your students understand the basics of the Tree of Reasoning.

Want the full Tree of Reasoning resource kit? Click Here!

You get the idea, right? Juuuust in case a step leaves you scratching your head, I'll take a moment to clarify the pieces here...

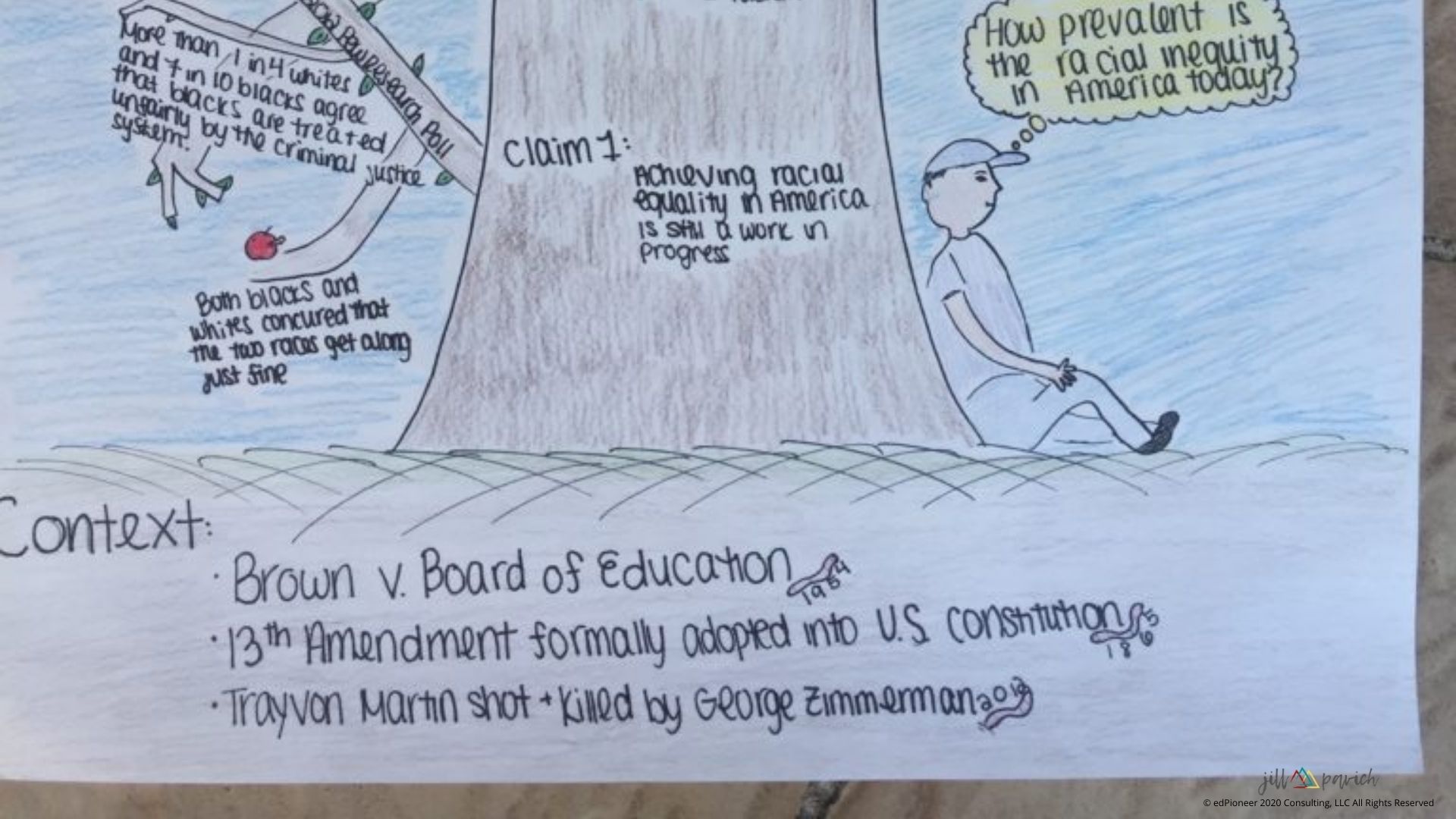

STEP 1: CONTEXT

First, let's talk about the foundation. Our writers typically come in with this belief that arguments operate in a vaccuum...as if there were no circumstances or outside forces influencing them. So it's our job to introduce them to a more panoramic view of arguments!

At the base of any argument, then, there's the context surrounding the issue.

For instance, if we're arguing about gun control laws, we can't ignore all that has happened in the recent past, those events that have undoubtedly shaped the way we view the topic at present. If we're going to argue about these laws, we'll have to consider tragedies as far back as say, Columbine in 1999, to more recent ones such as Marjory Stoneman Douglas.

In order to contextualize the issue, students should ask themselves:

- URGENCY...Why does this issue MATTER right now? Who cares? Why do we need to be reading about it? (URGENCY)

- LOCAL-TO-GLOBAL APPEAL...Where does this issue matter? Where in the world are we as concerned citizens (and eventually, how does that affect our perspective?)

- MOMENTUM...How long has this issue mattered? Where did this issue really take root in the past and how has it evolved or gained momentum to bring us into the present?

STEP 2: ARGUMENTATIVE CLAIM(S)

When it comes to claims, think of these as the 'big picture' points of view surrounding the argument (whereas the sub-claims are more specific). If the question is, "to what extent should we pursue hydrogen fuel cells as our primary energy source for transportation?", then the trunk's claim might either accept or deny this fuel source as a feasible alternative to traditional gas. [Keep in mind that the argument itself will obviously not be this black and white, but to argue, they'll need to pledge some allegiance to a side...]

In my own instruction, my students use the tree to build out multiple perspectives to an issue before they begin drafting their work and thereby forming their own opinion.

So either they have several sheets of 'trees' -- I call it their 'forest,' lol -- or they 'grow' two perspectives going up the trunk of one tree.

The student studying hydrogen fuel cells would have two (2) claims going up the trunk of his tree regarding pursuit (keeping in mind these don't have to just be black-and-white 'do or 'dont').

By the end of our research adventure, he'll draw his own conclusion, but in the meantime researches with an open mind...

Why, you ask?

A lot of times, if students are left to pick their own topic, they tend to pursue issues that are of genuine interest to them (at least, that is the hope!). And if they're genuinely interested in something, it's probably because they've had exposure to it before. And if they've had exposure to the issue before, chances are they have an opinion on it! (sheesh, sorry).

Long story short? I require them to look at both sides to avoid letting their own personal biases, preconceptions, and even misconceptions get in the way of good research, and because hey, they might even change their tune after a little surface work.

Besides, we've got zero time for rants.

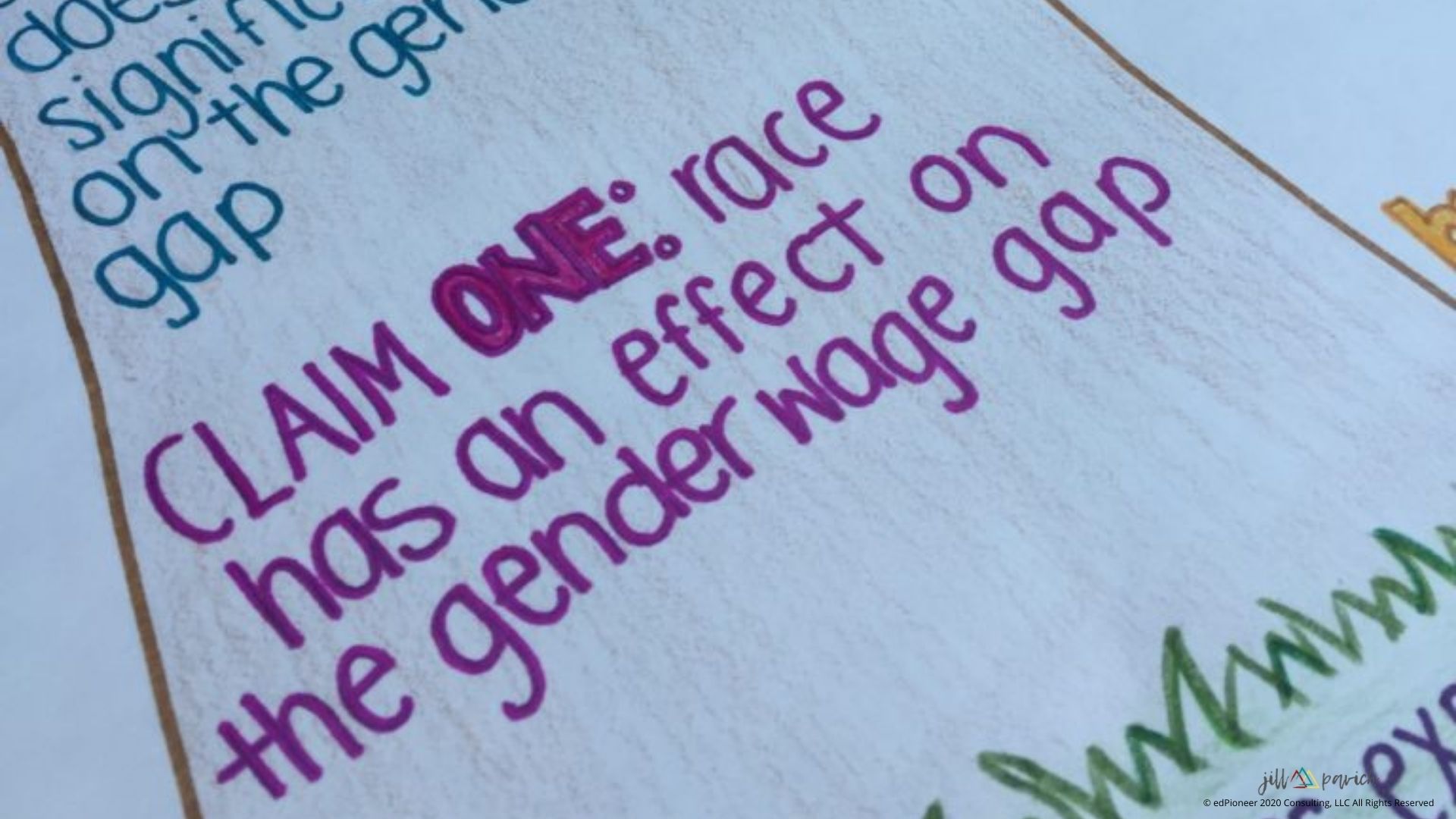

STEP 3: SUB-CLAIMS

As you may have guessed, sub-claims break the main, argumentative claim down more specifically.

CLAIM: We should not pursue hydrogen fuel cells as an alternative transportation fuel.

SUB-CLAIM 1: We shouldn't because it's too expensive.

These *perspectives* are the branches that hold the structure of the tree up; in research-speak, we like to think that these are the voices that are keeping the conversation going. An important point to raise here, though. I know it seems like the natural order would be:

- Identify sub-claim.

- Locate evidence to support.

But that isn't always the case, so I caution you not to fall into a rigid way of teaching this; in other words, avoid making this a formulaic thing. Plenty of students will gather a mound of evidence about their topic first, then after reading through it all, begin to see the big picture patterns emerging. And yes, these are perspectives rearing their rubric-savvy heads, the student sub-claims.

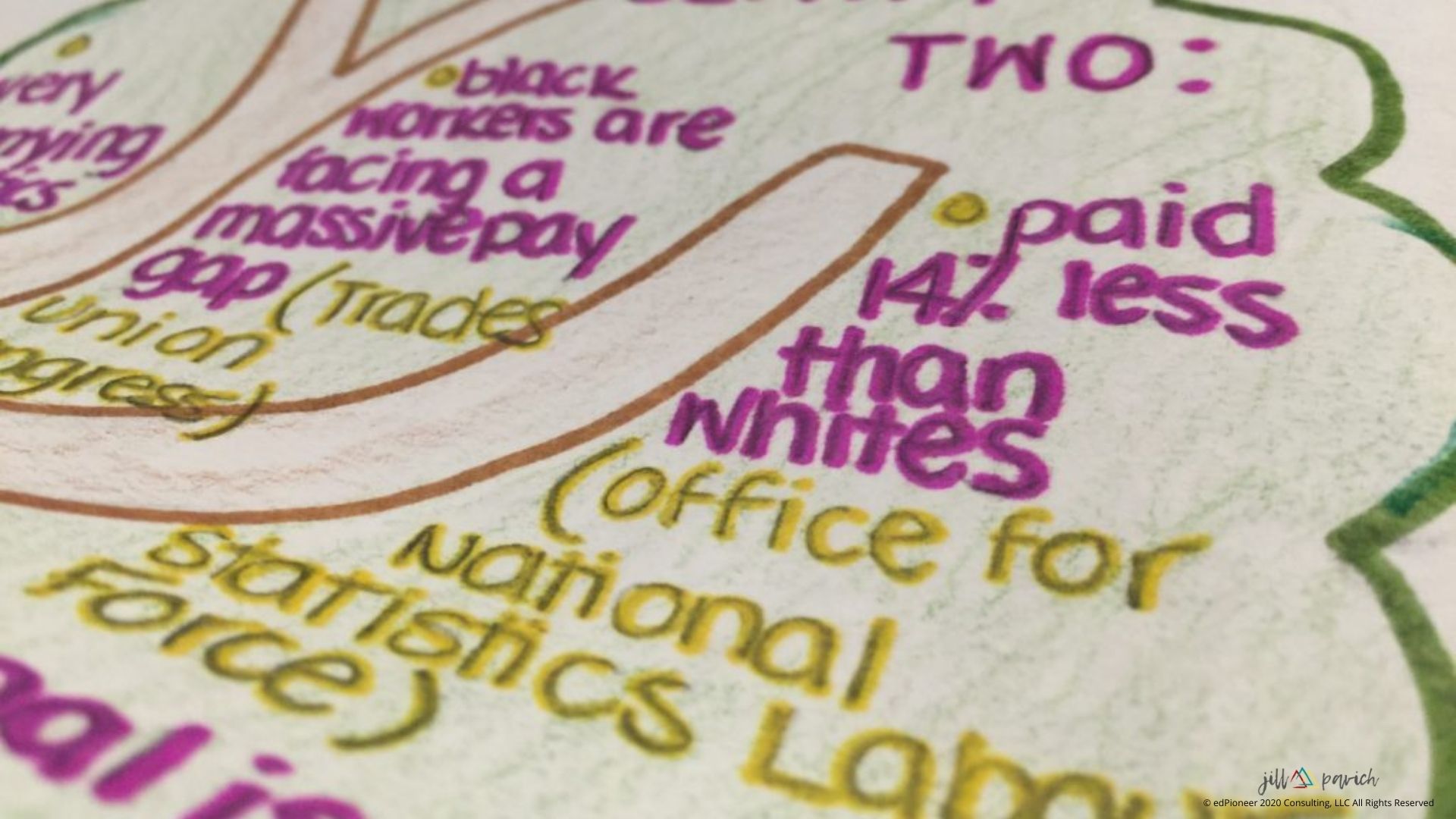

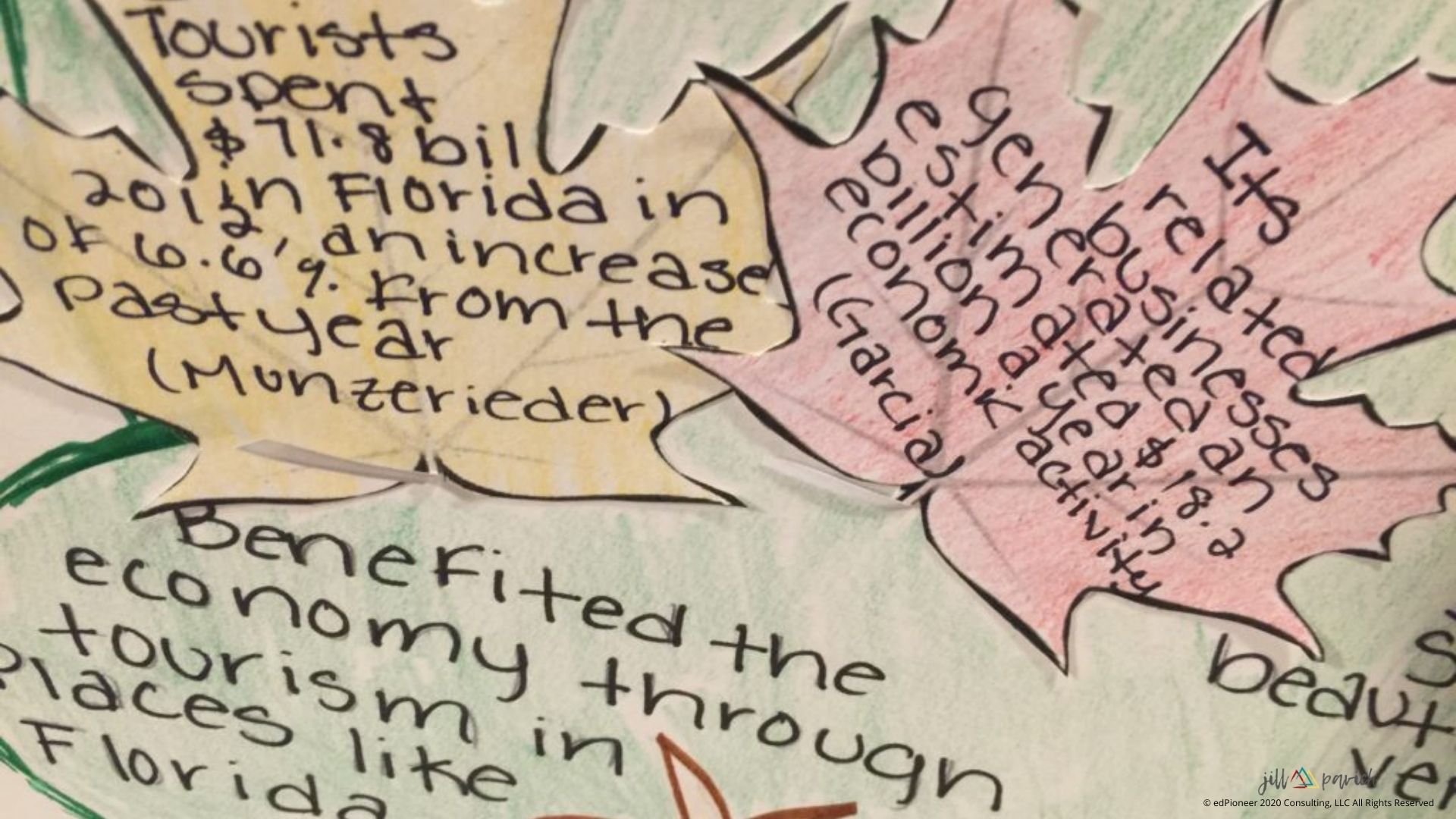

STEP 4: EVIDENCE

Our students are definitely off to a great start if they have their branches identified--or in other words, those big ideas that'll govern the argument--but if those branches have no leaves on them (aka, evidence), then this tree will start looking more like Charlie Brown's Christmas tree...and if you're wondering, no, that's not so good.

To help them spruce up their support, I guide my writers along with the following, simple probes:

- What big ideas keep cropping up in your research? (i.e. funding issues? cultural push-back? lack of public support? legislative barriers?)

- Do you have a range of sources who seem to agree? (multiple stakeholders/groups/entities from a number of diverse backgrounds and disciplines)

- Any sources who disagree with the sub-claim? (what are the opposing viewpoints, and how does this play a role in the strength of your own argument? How will you include this information without detracting from your own point?)

For opposing views, I like to have my students drop a bird on the branch with that point-counter input. It's kind of like, "yes, my branch says this and my leaves say that, BUT...a little birdie told me...so I have to take that into consideration too, I guess."

Bottom line, if your tree isn't FULL, if there are bare spots, they need to be patched in. And if the leaves are getting eaten alive by caterpillars (lots of holes, get it?), then you'll need to better protect these precious greens or prune them altogether.

INTELLECTUAL INTERLUDE

Once sub-claims are established, challenge your students to meaningfully number them. We want them to craft a logical progression of ideas and to begin to see a horizontal sequencing where one thing leads to another. For instance, if sub-claim one contends that hydrogen-fuel cells are too expensive, sub-claim two might dig into the lack of public support as a result. Cause. Effect. Connections among claims to build a line of reasoning. #clever

Not to mention, if you're an AP Seminar teacher, you'll need to school your kids on articulating this kind of argumentative design because it's actually part of their written exam.

Observe:

Explain the author’s line of reasoning by identifying the claims* used to build the argument and the connections between them. (6 points)

*Notice that the exam uses claims (generic), that they do not specify claims from sub-claims like we do on our tree, so just make sure that closer to the exam you clarify this with your kids. OR, if you'd rather just use the term "claims" and leave sub-claims behind, you can. In this case, you'd tell your students to indicate on the trunk which side of the argument they'll be arguing; the branches become the 'claims' as opposed to the sub-claims. Got it?

Yup. That's Q2 on the first part of the exam. It's no secret, but again, trust me when I say, it's no easy task to teach.

In fact, in teaching this course, I've come to find that no matter how many times I expose my students to this very question, they go running for the hills. Every. Single. Time.

"Pavich...what do you MEAN?!" accompanied by this crazed look in their eyes.

Having thought I'd beat them over the head with what is meant by this question, I find myself fighting to suppress the *eye roll* sigh * chest puff* sequence of non-verbals threatening to erupt.

Instead, I ask myself, how can I get them to see what I mean by 'line of reasoning'? Hence, the Reasoning Tree and the awesome academic fruit it bears.

Anywho...

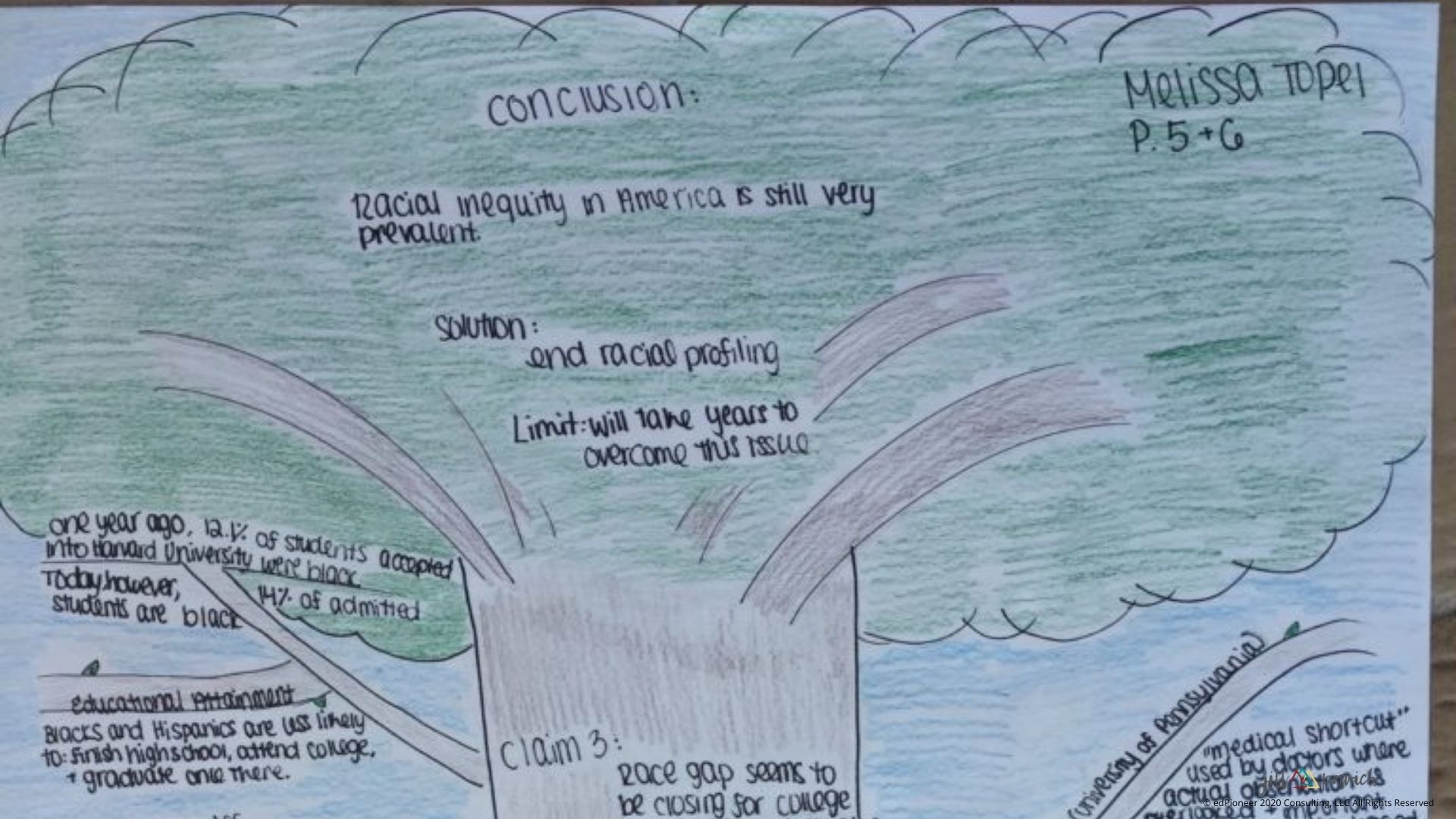

STEP 5: DRAWING CONCLUSIONS/OFFERING SOLUTIONS

If your students have grown their tree carefully, all of the branches and leaves will be reaching eagerly toward the sunlight. And that sunlight, my friends, will be the enlightening conclusions drawn from all their hard work. It's finally time to shed some light on the matter, and it's also a lightbulb moment for proposing solutions to the problems our issue causes.

The key here is that the leaves grow toward the light...that's how plants do it. They reach for that warm and sunny bliss that we know of in the logical world as clarity.

For our writers, if their sunshine moment at the end of the argument doesn't stem from the growth below, then it's NOT a logical conclusion to draw!

My students tend to do all the research and hard work but then revert back to the status quo opinion in the conclusion because they're not sure what to say. Here's a quick example to show how that goes down:

Let's say I'm a teacher (oh, wait...I am), and I'm researching whether or not the college diploma still has value in today's global market. All the evidence is pointing to NO, but since I'm a teacher, and I believe in higher education, my conclusion ends up saying, yes the diploma has value.

Not so fast! That's an example of how the leaves don't reach toward the sunlight.

Why do I speak in horticultural terms? Is it because I'm an utter cheeseball who laughs at her own, punny jokes? Obvi, that's certainly part of it. But I hope I've won enough credibility with you to say, TRUST ME, students will see these images for the rest of the year. So when you say to them...

- Did you lay the dirt?

- Did you decide on your trunk?

- Do you have a range of sturdy branches?

- Is your tree full or are you all Charlie Brown on me?

- Is your tree 'bird-friendly'?

- Check your partner to see if he/she has a caterpillar infestation.

- Are you talking to your plant each night, giving it TLC?

- Is your tree getting proper sunlight?

...they'll know EXACTLY what you mean. And they WON'T think you're crazy, either, lol.

So if you've made it this far in my whopper of a post, CONGRATS! You just learned how to grown your own Argumentus Reasonabis. Sweet!

If you would like the full Tree of Reasoning resource kit, click here!

Our first approach involved growing up, but get your demo hats on because now we're about to raze some arguments to the ground, crew.

Razing an Argument

Raze. Like, flatten. This next activity is all about deconstruction. Not that we aren't breaking down arguments into parts when we 'grow' them, but you get the playful idea ;-)

A second, awesome way for students to challenge themselves with the enigma that is 'line of reasoning' is to have them reverse engineer an essay. What is it that makes this thing tick?! Once again, it takes us back to the, 'wow, this guy killed it' sensation, but then it forces us to figure out WHY his argument was so stinkin' effective in the first place.

The plan is to offer you much more for this during the coming school year, but for now, here's a starter idea...

- Pull 13 students to form an Inner Circle.

- Form an Outer Circle around these kids and pair students accordingly (ideally, you have 26 kids, but you can always assign multiple paragraphs to a single pair of students).

- Inner Circle member (1A) reads the first paragraph aloud.

- Outer Circle member (1B) articulates the author's purpose in writing paragraph (1).

- Inner Circle members other than (1A) can add to this response as necessary.

- Teacher records ideas on a Google Doc overhead.

- Repeat until you've reached paragraph (13) and finished the essay.

- Congrats, you've just reverse-engineered an essay!

- Now observe the line of reasoning...how does the student order his/her claims? Why does he/she do this? What effect does it have? Could he/she have done something differently in this regard?

- Critique further. Consider the dirt, the trunk, the branches, the leaves, the birds, the caterpillars...you get the idea ;-)

GOAL? Argumentative Mindfulness. Yes!!!!

Well, it's been a long haul, but thanks for stickin' with me! I hope this post helps you find your student-centered footing when it comes to teaching lines of reasoning!

Have any fun today? Learn anything new or stumble across anything useful?

Great! Spread the word! Tell your research-readin', essay-teachin' friends!

Yours in Education & All Things Innovative,

Jill